The longest I lived anywhere was Cincinnati, where I settled in 1982.

Now, Jeanne and I are heading out to Charlotte, North Carolina, a city where I spent most of my high school years, where I worked as a political reporter for the Charlotte Observer, where I worked on an (unsuccessful) U.S. Senate campaign, and where my parents passed away and are buried at nearby Belmont Abbey College, along with my oldest brother. My other brother died in a Charlotte hospice in 2015. I guess I will find out whether North Carolina writer Tom Wolfe was right in naming one of his novels “You Can’t Go Home Again.”

Here’s hoping we will prove Wolfe wrong. Jeanne has a new position doing marketing and PR for an up-and-coming software developer. We have dear nephews close by. We are also empty nesters, but there is plenty in the Charlotte area to keep us both busy and entertained. Besides, we will be only hours away from the NC/SC coast.

Still, Cincinnati is much on my mind. I leave the “Queen City” with a myriad of thoughts and feelings, some of which I’d like to share. If you don’t mind.

Cincinnati is a wonderful, perhaps ideal, place to raise a family. Large, but not overwhelming. Ripe with a garden variety of singular townships, neighborhoods and communities — each distinctive and each with its own charms. My first stop was in bucolic Wyoming, and since 1992, sprawling Anderson Township. Two completely different places, but both with just the right mix of people, attractions and schools. I made friends in both places, who I will always cherish.

Cincinnati also is blessed by a beautiful location at a crook in the Ohio River. If you go atop the  Carew Tower, the City’s tallest building, the horizon is flat as a pancake. But a maze of valleys carved by tributaries of the Ohio has given Cincinnati steep hills and plenty of areas unfit for development. The result: vast park land and forest within the city limits.

Carew Tower, the City’s tallest building, the horizon is flat as a pancake. But a maze of valleys carved by tributaries of the Ohio has given Cincinnati steep hills and plenty of areas unfit for development. The result: vast park land and forest within the city limits.

The Ohio River is wide and rapid as it flows west and south through the area. It was an early highway of western expansion, with riverboats as the preferred mode of transport. As you drive along Columbia Parkway, which contours the river’s course and look across to Kentucky, Germany’s Rhine River comes to mind, an appropriate comparison since much of the area’s earliest settlers were German immigrants.

Cincinnati and Charlotte both have NFL teams, but only Cincinnati has major league baseball, the beloved Reds. It’s a good thing they are beloved, because lately, they’ve not been very good. Charlotte has NBA basketball, however, owned by Michael Jordan, so there’s that. It is rumored that Cincinnati also has an NFL-caliber football team.

For most of my time in Cincinnati, I worked for Kroger in its headquarters down on Vine St. Kroger in the early 1980’s was a fast-growing, increasingly national food retailer that in 1983 celebrated its 100th anniversary. My job was to represent the company to the news media as corporate PR director, and also help write speeches, address controversies, and generally speak and write transparently about a business that touched nearly every household in Cincinnati and dozens of other cities.

The guy I worked with and reported to was Jack Partridge, who recruited me from Washington, where I had worked in Jimmy Carter’s Administration. To say that we were always on the same page would be an understatement and despite our differing political views. He and I looked at our responsibilites with complementary eyes, and we felt we were serving not just our business, but the entire community. (Jack and I were early members of Leadership Cincinnati, and Kroger graciously assigned me to work on important civic matters, such as the 1991 Buenger Report on Cincinnati Public Schools).

The guy I worked with and reported to was Jack Partridge, who recruited me from Washington, where I had worked in Jimmy Carter’s Administration. To say that we were always on the same page would be an understatement and despite our differing political views. He and I looked at our responsibilites with complementary eyes, and we felt we were serving not just our business, but the entire community. (Jack and I were early members of Leadership Cincinnati, and Kroger graciously assigned me to work on important civic matters, such as the 1991 Buenger Report on Cincinnati Public Schools).

Jack, in turn, reported to Kroger’s CEO, Lyle Everingham, a decent, plain-spoken, hard-working and astute executive who believed in delegating responsibility and expecting superior results. Some may recall that in 1988, Kroger came very close to being taken over by outside investors. Lyle, his top managers and the Board thought the idea stank to high heaven, and so they put together a financial restructuring plan that saved the company’s independence. The plan was created in part by a handful of top executives, including Bill Sinkula, Larry Kellar and one Rodney McMullen — now Kroger’s CEO.

But the plan necessitated a widespread cutback in expenses and, as a consequence, hundreds of folks in G.O., including some of my closest friends, lost their jobs. The company continued to prosper, but for old salts like Jack and me, it was never quite the same.

Skyline. As in chili. Across Vine from Kroger’s office was a Skyline Chili parlor, where Kroger people often found themselves at lunchtime. Shortly after starting work, I went to Skyline to be initiated into this somewhat mysterious and legendary concoction that, to many, represents the essence of Cincinnati. “Mikey, he likes it,” my companions laughed, mimicking a popular TV ad for cereal. I did, and still do. I will miss Skyline in North Carolina, which is more of a barbecue kind of place. I will also miss explaining to people what the hell a three-way is.

laughed, mimicking a popular TV ad for cereal. I did, and still do. I will miss Skyline in North Carolina, which is more of a barbecue kind of place. I will also miss explaining to people what the hell a three-way is.

In 1998, I left Kroger to start my own communications consulting firm, called (not very creatively) Bernish Communications. My first client was Kroger, and over time I did work for Harris Teeter in Charlotte (now part of Kroger), as well as Publix in Florida. I also worked for a Canadian firm that launched one of the first self-scanning checkout systems, and a manufacturer of paper-making equipment based in northern Ohio.

Around this time, I was contacted by a community leader, Chip Harrod, who asked my opinion about an idea of his to create a museum about the Underground Railroad on the banks of the Ohio River. This region was a significant crossing point for slaves fleeing from Kentucky and further South (immortalized in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin). I told Chip the idea appealed to me and next thing I knew, I was on the founding board for the fledgling project.

The Freedom Center exists today, a yearly destination for thousands of elementary and high school students bussed in to learn about America’s prolonged cancer — slavery. Yet It has been decidedly a sore point for some in Cincinnati who believe the museum is too grandiose and offers too negative a theme to ever be popular. But to others, myself included, the Freedom Center ultimately represents an important attempt to help modern-day Americans (and others) understand the many ways slavery degrades and corrupts the essentials binding together moral, successful societies. Yes, much of the content in the museum is difficult and unpleasant. Yet at the same time, the triumph of the human spirit, as represented by those who attempted to flee the shackles of bondage, and those who helped their escape, is an eternally uplifting message — the “arc of moral history,” in the quoted words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., “is always bending towards justice.”

The Freedom Center, let it be said, likely would not exist were it not for John and Francie Pepper and former federal appeals court judge Nathaniel Jones. The Peppers truly are citizens in the most fundamental sense of the word, in which service to others and playing things forward are firmly-held values and a way of life. Judge Jones is a moral beacon of grace and guts.

The Freedom Center, let it be said, likely would not exist were it not for John and Francie Pepper and former federal appeals court judge Nathaniel Jones. The Peppers truly are citizens in the most fundamental sense of the word, in which service to others and playing things forward are firmly-held values and a way of life. Judge Jones is a moral beacon of grace and guts.

One area of civic life that did reel me in was the City’s superb arts organizations. This involvement went well beyond an annual contribution to the Fine Arts Fund. I served on the Chamber Orchestra Board for a time, and spent about two years raising money for the late Eric Kunzels’s dream of a new building for the unique and inspiring School of the Creative and Performing Arts. Kunzel was a life force, a walking magnetic field, and working with him was a life lesson in the power of an idea. The new SCPA is not physically attached to Music Hall, as Eric hoped, but it’s just down the street, and I’m sure he’d be pleased with the result.

I also dearly loved the Symphony, despite the cramped seating in the old Music Hall.  After an inspiring performance by the CSO, I would joyously but slowly limp out to my car. Perhaps my most treasured moment was attending the CSO’s scheduled event not long after 9/11. Maestro Paavo Jarvi (leading the orchestra for the first time) conducted a somber yet somehow affirming performance that had everyone in the hall lost in thought and yet yearning for human contact that classical music often offers. It was a singular moment; it didn’t last long, unfortunately, as America soon descended into war, retribution and gnawing fear.

After an inspiring performance by the CSO, I would joyously but slowly limp out to my car. Perhaps my most treasured moment was attending the CSO’s scheduled event not long after 9/11. Maestro Paavo Jarvi (leading the orchestra for the first time) conducted a somber yet somehow affirming performance that had everyone in the hall lost in thought and yet yearning for human contact that classical music often offers. It was a singular moment; it didn’t last long, unfortunately, as America soon descended into war, retribution and gnawing fear.

After a couple of turns on the Freedom Center Board, I joined the Freedom Center staff in 2004 just in time to assist in the grand opening (remember Oprah Winfrey’s grand and elegant participation down on the riverfront). Later, I helped create a new, permanent exhibit about human trafficking, which is the despicable practice of modern-day slavery. It is, if I may say so, the best thing I have ever done. You should go see it.

I’ve continued to consult in a joint endeavor with Gale Prince, a former Kroger colleague and one of the nation’s leading experts on food safety. It’s been fun to dip back into the food sector.

And here we are, relocated to Charlotte, a much different, much larger city that also has been transformed by global economic tides. When I was a high school student here, at a tiny, all-boys Catholic outpost run by the Marianist Brothers, Charlotte was kind of a boastful backwater, a place that mid-level executives came to on their way up the corporate ladder to Atlanta or Dallas or Frankfurt. No longer. Today, Charlotte is a booming metropolis that has spilled over into South Carolina. It is the nation’s second largest banking center, after only the Big Apple, and with the skyscrapers and inflated home prices that come with explosive growth. Catholic High is now located in a large campus-like setting with high academic standards and sports excellence. Old Coach Willie Campagna would be astounded.

And here we are, relocated to Charlotte, a much different, much larger city that also has been transformed by global economic tides. When I was a high school student here, at a tiny, all-boys Catholic outpost run by the Marianist Brothers, Charlotte was kind of a boastful backwater, a place that mid-level executives came to on their way up the corporate ladder to Atlanta or Dallas or Frankfurt. No longer. Today, Charlotte is a booming metropolis that has spilled over into South Carolina. It is the nation’s second largest banking center, after only the Big Apple, and with the skyscrapers and inflated home prices that come with explosive growth. Catholic High is now located in a large campus-like setting with high academic standards and sports excellence. Old Coach Willie Campagna would be astounded.

I will definitely be a tiny cog in a big wheel here. In Cincinnati, I was never a mover and shaker. But I was sometimes in the room, like Zelig, with many who were. During most of Cincinnati’s history hometown companies exerted an outsized, albeit mostly beneficial, influence on local affairs. Chief among them, of course, is Procter & Gamble, which to many is synonymous with the city. Political, religious, arts and cultural leaders generally sought P&G’s views out of the Company’s well-earned respect, the enormous  resources it could direct to civic endeavors, and the generous executive involvement it could bring to any significant community need. Another influencer is the Cincinnati Business Committee, or CBC, made up exclusively of company chieftains, where huge and lasting decisions are reviewed alongside the normal political and governmental channels.

resources it could direct to civic endeavors, and the generous executive involvement it could bring to any significant community need. Another influencer is the Cincinnati Business Committee, or CBC, made up exclusively of company chieftains, where huge and lasting decisions are reviewed alongside the normal political and governmental channels.

Local companies are critical drivers of economic growth and supporters of civic projects but these days, Cincinnati-based firms have a lot on their plate well outside the Queen City. Like businesses everywhere, Cincinnati companies must serve a national, even global audience and confront strenuous global competition. Kroger, to mention an obvious example, is a major presence in cities much larger than Cincinnati, including Atlanta, Los Angeles, Denver and Houston. Or take Fifth Third, once a proud hometown bank. Today, it operates in large swathes of the Midwest and South, while back home in southern Ohio, it must confront major competitors like US Bank and PNC — from hated Pittsburgh, no less! Fifth Third operates in Charlotte, by the way.

The impact of these swirling trends has forced businesses to broaden their horizons. Companies with deep local roots, such as Cintas or Fifth Third, must increasingly allocate charitable and civic resources in other places, as well. At the same time, public companies face constant challenges from shareholders, often hedge funds, that demand ever-rising profits. This has an impact, sometimes direct, on how much corporations invest in communities.

All this really means that Cincinnati’s economy — and its very way of life — is caught up as never before in the world beyond this corner of Ohio. Things have really opened up locally (think OTR or the riverfront);  the City is no longer 10 years behind the rest of the country, as Mark Twain famously quipped. Its future is bright, but it must do more to retain and attract young professionals who often see their future as residing in Chicago, or Boston, or Austin.

the City is no longer 10 years behind the rest of the country, as Mark Twain famously quipped. Its future is bright, but it must do more to retain and attract young professionals who often see their future as residing in Chicago, or Boston, or Austin.

Charlotte, like Cincinnati and many other urban areas, has developed energetic, vibrant suburbs surrounding the central city core. In Charlotte, development is best described as rampant, whereas in the areas around Cincinnati, growth is more measured but plainly obvious when, for example, you drive north on Interstate 75 and see that Cincinnati’s suburbs are fast encroaching on Dayton’s.

One troubling factor, however, is that the suburban communities seem largely detached from the core urban areas. Mason could just as easily be in Kansas or Pennsylvania. Fort Mill, S.C. looks like it would fit nicely into suburban Dallas. Suburbs are where the fast food and casual dining chains, along with auto supply and tire discounters ply their trades, and traffic is on the whole terrible. Few of the suburbs feel at all unique, as a result. These trends are perhaps irreversible, although Charlotte is looking at dramatically expanding its Lynx commuter train service (that now connects “Uptown” to Charlotte’s South End) north to the Lake Norman area, west to the airport, southeast, etc. Cincinnati has an urban train of sorts, but it is doubtful it will soon or ever be expanded.

But at least Charlotte has city-county government. Cincinnati does not, and this is a limiting factor to its ability to connect suburbs to the city and enable workers to easily commute to jobs in the suburbs. Clearly, visionary political leadership is needed.

Well, Cincinnati’s future will no longer affect Jeanne and me. Charlotte and Mecklenburg County operate a combined city-county government that has been in place for decades. It is by no means a panacea; Charlotte is plagued with overwhelming traffic woes, under-performing, crowded schools, and suburban sprawl that is unstoppable and shorn of charm. Its wish to expand the Lynx system is, at the moment, stymied by the lack of funding sources.

So, I am transitioning from one city where I lived for a quarter of a century to another city where I lived through my high school, college and early professional career. As a consequence, I sort of feel like I am living in two places simultaneously, with one foot firmly planted in the past and the other tentatively positioned to explore whatever future is ahead.

Folks, this is hard. Even as I make new friends and re-aquaint with old high school buds, I will long feel the tug of strong emotional attachments to the people I have known, worked with and grown close to in Cincinnati over the years. If I mentioned even one such person or family, such as Peter Larkin, John Barnett and Jim McIntire from Kroger days, or Heather Hill neighbors Bridget and Tom Breitenbach, Harry and Ginny DeMaio, Malinda and Wayne Price, the Annable’s, Barb and Sam Gamble, or just plain friends Jamie Glavic, or Norma Petersen or Ken Schonberg, Ross Wales and Richard and Penny Hoskin, I would be listing several hundred more names, and your eyes would glaze over.

So I won’t do that. Instead, I wish all of you who knew us a fond farewell — until next time. As a nation, we are crossing through a rough patch, divided by mistrust, ready to argue at the drop of a hat, using ever coarser language and behaviors. But there is no doubt in my mind that America will survive and prosper. Whenever I get down, I try to think of Maestro Jarvi, holding, ever so slightly, the last notes of Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings. Music Hall was packed that night a little over a week after 9/11; for that single moment, no one in that crowd was a stranger. Everyone was holding up one another. That’s what we should strive for.

In the meantime, I hope we can all engage in empathy and respect, and encourage peals of laughter. Kindness and good manners will get you a long way, my Mom used to say, and while I’ve not often showed those attributes, it still strikes me as good advice.

Adieu!

Canes are perhaps best known as props for dancers, like the incomparable Fred Astaire, who could glide across the stage effortlessly tap dancing while holding and twirling a cane. The irony of such an image needs no elaboration.

Canes are perhaps best known as props for dancers, like the incomparable Fred Astaire, who could glide across the stage effortlessly tap dancing while holding and twirling a cane. The irony of such an image needs no elaboration. Psychologically, needing a cane is somewhere between embarrassing and unnerving. I hate that I need it because even at my age (low 70’s), I think in my mind that I am robust and agile. It is unnerving because we all want to put off the inevitable end, and we flee from its approaching menace. The cane is, to me, an avatar of impending doom.

Psychologically, needing a cane is somewhere between embarrassing and unnerving. I hate that I need it because even at my age (low 70’s), I think in my mind that I am robust and agile. It is unnerving because we all want to put off the inevitable end, and we flee from its approaching menace. The cane is, to me, an avatar of impending doom. Stonehenge and Bath. These stops, plus lunches in pubs, dinners in delightful but pricey restaurants, and numerous rides in the iconic black beetle cabs or on the London Underground, enabled me to see a major global city at perhaps its most vulnerable since the Blitz. I came away thinking that London is cheekily self-confident even as it denizens express great uncertainty about its future should Brexit actually happen — if it ever comes to pass.

Stonehenge and Bath. These stops, plus lunches in pubs, dinners in delightful but pricey restaurants, and numerous rides in the iconic black beetle cabs or on the London Underground, enabled me to see a major global city at perhaps its most vulnerable since the Blitz. I came away thinking that London is cheekily self-confident even as it denizens express great uncertainty about its future should Brexit actually happen — if it ever comes to pass. kinds and price levels. It is a kaleidoscope that never stops turning. It has sprouted high rise office and apartment buildings that contrast (and in some cases, diminish) the existing and aging facades of England’s adventurous past.

kinds and price levels. It is a kaleidoscope that never stops turning. It has sprouted high rise office and apartment buildings that contrast (and in some cases, diminish) the existing and aging facades of England’s adventurous past. challenges every notion you’ve ever had of that master of the English idiom. Among the portraits still on view is one of Sir Oswald Mosley, an aristocratic Fascist who liked to spew anti-Semitic tirades in Jewish neighborhoods in the East End wearing his own self-styled Nazi uniform. Another is of Sir Douglas Haig, the British general who in World War I sent a generation of young men to their deaths. No outrage, no endemic of grievance, as in America, threatens the removal of these loathed figures.

challenges every notion you’ve ever had of that master of the English idiom. Among the portraits still on view is one of Sir Oswald Mosley, an aristocratic Fascist who liked to spew anti-Semitic tirades in Jewish neighborhoods in the East End wearing his own self-styled Nazi uniform. Another is of Sir Douglas Haig, the British general who in World War I sent a generation of young men to their deaths. No outrage, no endemic of grievance, as in America, threatens the removal of these loathed figures. I made a special effort to visit St. Paul’s Cathedral simply because of how struck I had been as a youngster at the photograph of the church’s magnificent dome emerging from the smoke of a Luftwaffe bombing raid. It is still there, and likely will still be there after the next Ice Age crushes most everything in its path.

I made a special effort to visit St. Paul’s Cathedral simply because of how struck I had been as a youngster at the photograph of the church’s magnificent dome emerging from the smoke of a Luftwaffe bombing raid. It is still there, and likely will still be there after the next Ice Age crushes most everything in its path. like balloons, needing to land but seeing nothing below but treacherous forest. In the end, however, there certainly is enough grit and determination in both countries to find a way ahead. England and America are different in many respects, but alike in the belief in the enduring strength of their people to carry on, push through and find peace and security for all within their bounds.

like balloons, needing to land but seeing nothing below but treacherous forest. In the end, however, there certainly is enough grit and determination in both countries to find a way ahead. England and America are different in many respects, but alike in the belief in the enduring strength of their people to carry on, push through and find peace and security for all within their bounds. I share my reactions to this book with not a little trepidation. In part that’s because I don’t truly identify with religion — that is

I share my reactions to this book with not a little trepidation. In part that’s because I don’t truly identify with religion — that is  Carew Tower, the City’s tallest building, the horizon is flat as a pancake. But a maze of valleys carved by tributaries of the Ohio has given Cincinnati steep hills and plenty of areas unfit for development. The result: vast park land and forest within the city limits.

Carew Tower, the City’s tallest building, the horizon is flat as a pancake. But a maze of valleys carved by tributaries of the Ohio has given Cincinnati steep hills and plenty of areas unfit for development. The result: vast park land and forest within the city limits.

The guy I worked with and reported to was Jack Partridge, who recruited me from Washington, where I had worked in Jimmy Carter’s Administration. To say that we were always on the same page would be an understatement and despite our differing political views. He and I looked at our responsibilites with complementary eyes, and we felt we were serving not just our business, but the entire community. (Jack and I were early members of Leadership Cincinnati, and Kroger graciously assigned me to work on important civic matters, such as the 1991 Buenger Report on Cincinnati Public Schools).

The guy I worked with and reported to was Jack Partridge, who recruited me from Washington, where I had worked in Jimmy Carter’s Administration. To say that we were always on the same page would be an understatement and despite our differing political views. He and I looked at our responsibilites with complementary eyes, and we felt we were serving not just our business, but the entire community. (Jack and I were early members of Leadership Cincinnati, and Kroger graciously assigned me to work on important civic matters, such as the 1991 Buenger Report on Cincinnati Public Schools). laughed, mimicking a popular TV ad for cereal. I did, and still do. I will miss Skyline in North Carolina, which is more of a barbecue kind of place. I will also miss explaining to people what the hell a three-way is.

laughed, mimicking a popular TV ad for cereal. I did, and still do. I will miss Skyline in North Carolina, which is more of a barbecue kind of place. I will also miss explaining to people what the hell a three-way is. The Freedom Center, let it be said, likely would not exist were it not for John and Francie Pepper and former federal appeals court judge Nathaniel Jones. The Peppers truly are citizens in the most fundamental sense of the word, in which service to others and playing things forward are firmly-held values and a way of life. Judge Jones is a moral beacon of grace and guts.

The Freedom Center, let it be said, likely would not exist were it not for John and Francie Pepper and former federal appeals court judge Nathaniel Jones. The Peppers truly are citizens in the most fundamental sense of the word, in which service to others and playing things forward are firmly-held values and a way of life. Judge Jones is a moral beacon of grace and guts. After an inspiring performance by the CSO, I would joyously but slowly limp out to my car. Perhaps my most treasured moment was attending the CSO’s scheduled event not long after 9/11. Maestro Paavo Jarvi (leading the orchestra for the first time) conducted a somber yet somehow affirming performance that had everyone in the hall lost in thought and yet yearning for human contact that classical music often offers. It was a singular moment; it didn’t last long, unfortunately, as America soon descended into war, retribution and gnawing fear.

After an inspiring performance by the CSO, I would joyously but slowly limp out to my car. Perhaps my most treasured moment was attending the CSO’s scheduled event not long after 9/11. Maestro Paavo Jarvi (leading the orchestra for the first time) conducted a somber yet somehow affirming performance that had everyone in the hall lost in thought and yet yearning for human contact that classical music often offers. It was a singular moment; it didn’t last long, unfortunately, as America soon descended into war, retribution and gnawing fear. And here we are, relocated to Charlotte, a much different, much larger city that also has been transformed by global economic tides. When I was a high school student here, at a tiny, all-boys Catholic outpost run by the Marianist Brothers, Charlotte was kind of a boastful backwater, a place that mid-level executives came to on their way up the corporate ladder to Atlanta or Dallas or Frankfurt. No longer. Today, Charlotte is a booming metropolis that has spilled over into South Carolina. It is the nation’s second largest banking center, after only the Big Apple, and with the skyscrapers and inflated home prices that come with explosive growth. Catholic High is now located in a large campus-like setting with high academic standards and sports excellence. Old Coach Willie Campagna would be astounded.

And here we are, relocated to Charlotte, a much different, much larger city that also has been transformed by global economic tides. When I was a high school student here, at a tiny, all-boys Catholic outpost run by the Marianist Brothers, Charlotte was kind of a boastful backwater, a place that mid-level executives came to on their way up the corporate ladder to Atlanta or Dallas or Frankfurt. No longer. Today, Charlotte is a booming metropolis that has spilled over into South Carolina. It is the nation’s second largest banking center, after only the Big Apple, and with the skyscrapers and inflated home prices that come with explosive growth. Catholic High is now located in a large campus-like setting with high academic standards and sports excellence. Old Coach Willie Campagna would be astounded. resources it could direct to civic endeavors, and the generous executive involvement it could bring to any significant community need. Another influencer is the Cincinnati Business Committee, or CBC, made up exclusively of company chieftains, where huge and lasting decisions are reviewed alongside the normal political and governmental channels.

resources it could direct to civic endeavors, and the generous executive involvement it could bring to any significant community need. Another influencer is the Cincinnati Business Committee, or CBC, made up exclusively of company chieftains, where huge and lasting decisions are reviewed alongside the normal political and governmental channels. the City is no longer 10 years behind the rest of the country, as Mark Twain famously quipped. Its future is bright, but it must do more to retain and attract young professionals who often see their future as residing in Chicago, or Boston, or Austin.

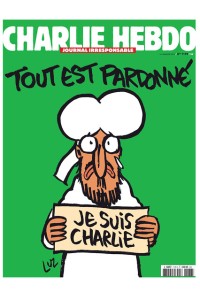

the City is no longer 10 years behind the rest of the country, as Mark Twain famously quipped. Its future is bright, but it must do more to retain and attract young professionals who often see their future as residing in Chicago, or Boston, or Austin. veils by Muslim school girls) appears in retrospect to be symptomatic of a smoldering fire that eventually consumed Charlie Hebdo. As the publication attacked Roman Catholicism, Judaism, and Islam, among many other targets, it infuriated disaffected French Muslims by publishing satirical images of the prophet Muhammed, which for many Muslims is the ultimate insult. We know the rest of the story. If disaffected Islam men and women continue to join or are recruited into terrorist cells that promote violence and nihilism under the banner of “faith,”what is the future for France, Europe, and America?

veils by Muslim school girls) appears in retrospect to be symptomatic of a smoldering fire that eventually consumed Charlie Hebdo. As the publication attacked Roman Catholicism, Judaism, and Islam, among many other targets, it infuriated disaffected French Muslims by publishing satirical images of the prophet Muhammed, which for many Muslims is the ultimate insult. We know the rest of the story. If disaffected Islam men and women continue to join or are recruited into terrorist cells that promote violence and nihilism under the banner of “faith,”what is the future for France, Europe, and America?